Science Museum: Exploring the History of Medicine

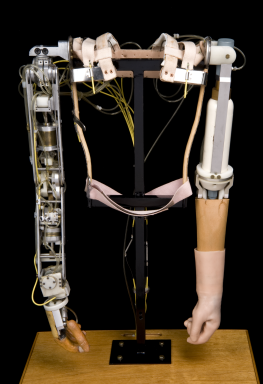

Pair of artificial arms for a child, Roehampton, England, 1964

The thalidomide disaster is one of the darkest episodes in pharmaceutical research history. The drug was marketed as a mild sleeping pill safe even for pregnant women. However, it caused thousands of babies worldwide to be born with malformed limbs. The damage was revealed in 1962. Before then, every new drug was seen as beneficial. Now there was suspicion and rigorous testing.

The development and sale of thalidomide

Thalidomide was developed in the 1950s by the West German pharmaceutical company Chemie Grünenthal GmbH to expand the company’s product range beyond antibiotics. It was an anticonvulsive drug, but instead it made users sleepy and relaxed. It seemed a perfect example of newly fashionable tranquilisers.

During patenting and testing, scientists realised it was practically impossible to achieve an LD50 level, or deadly overdose, of the drug. Animal tests did not include tests looking at the effects of the drug during pregnancy. The apparently harmless thalidomide was licensed in July 1956 for prescription-free over-the-counter sale in Germany and most European countries. The drug also reduced morning sickness, so it became popular with pregnant women.

First suspicions and the disaster

By 1960 doctors were concerned about possible side effects. Some patients had nerve damage in their limbs after long-term use. Grünenthal did not provide convincing clinical evidence to refute concerns. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s drug examiner Frances Oldham Kelsey did not approve the drug for use.

There was an increase in births of thalidomide-impaired children in Germany and elsewhere. However, no link with thalidomide was made until 1961. The drug was only taken off the market after the German Widukind Lenz and the Australian William McBride independently suggested the link. Over 10,000 children were born with thalidomide-related disabilities worldwide. Well-known people in the UK affected by thalidomide include actor and writer Mat Fraser.

The aftermath and thalidomide’s controversial rehabilitation

There was a long criminal trial in Germany and a British newspaper campaign. They forced Grünenthal and its British licensee, the Distillers Company, to financially support victims of the drug. Thalidomide led to tougher testing and drug approval procedures in many countries, including the United States and the United Kingdom.

In 1964 a leprosy patient at Jerusalem’s Hadassah University Hospital was given thalidomide when other tranquilisers and painkillers failed. The Israeli doctor Jacob Sheskin noticed the drug also reduced other leprosy symptoms. Research into thalidomide’s effects on leprosy resulted in a 1967 World Health Organisation (WHO) clinical trial. Positive results saw thalidomide used against leprosy in many developing countries. It is also used successfully to control some AIDS-related conditions, and its effects on various cancers are under investigation.

The renewed use of thalidomide remains controversial. The positive effects are undeniable. However, there is a risk of new thalidomide births, particularly in countries where controls may not be efficient. Black-market trade of unlicensed thalidomide by people with leprosy may increase the risks.

Related Objects

Pair of artificial arms for a child, Roehampton, England, 1964

Can one technology rectify the harm done by another? In the late 1950s and early 1960s, thousands of children across the world were born with malformed limbs because their mothers had taken a new drug known as thalidomide to counteract morning sickness and aid sleep. In Britain, one of the government’s responses was to fund the design of special prosthetic limbs for the many young children affected. Here is a pair of gas-powered arms made for a small child by the Steeper company. As children grow so quickly, this may have been the second or even third set they had worn. Their first pair were likely to have been much simpler, with doll-like plastic hands and very basic arm movements. This set is much more sophisticated, with arms that have pincer-like hook endings which could swivel and grip. Movements controlled by the child’s own short limbs or shoulders touching against sensitive valves on the inner surface of the ‘jacket’. However, there was a limit to what you could really do with them. Although these experimental limbs allowed children to do certain things for themselves, it’s debatable whether they gained any more independence than they would otherwise have done. Wearing them could be hot and very uncomfortable and regular re-fittings and adjustments were needed as the child grew. In the end, they were virtually all discarded by the time the children reached their teens.

Can one technology rectify the harm done by another? In the late 1950s and early 1960s, thousands of children across the world were born with malformed limbs because their mothers had taken a new drug known as thalidomide to counteract morning sickness and aid sleep. In Britain, one of the government’s responses was to fund the design of special prosthetic limbs for the many young children affected. Here is a pair of gas-powered arms made for a small child by the Steeper company. As children grow so quickly, this may have been the second or even third set they had worn. Their first pair were likely to have been much simpler, with doll-like plastic hands and very basic arm movements. This set is much more sophisticated, with arms that have pincer-like hook endings which could swivel and grip. Movements controlled by the child’s own short limbs or shoulders touching against sensitive valves on the inner surface of the ‘jacket’. However, there was a limit to what you could really do with them. Although these experimental limbs allowed children to do certain things for themselves, it’s debatable whether they gained any more independence than they would otherwise have done. Wearing them could be hot and very uncomfortable and regular re-fittings and adjustments were needed as the child grew. In the end, they were virtually all discarded by the time the children reached their teens.

Complete arm prosthesis, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1979

Movements of this mobile arm prosthesis are controlled by movements of the muscles around the child’s shoulder blades. These movements are powered by compressed carbon dioxide. The gas is stored in cylinders in the ‘passive’ arm. An active child might use two gas cylinders per day. Such limbs were fitted to children from 18 months upwards. The arm prosthesis was developed by the Orthopaedic Bioengineering Unit at Prin-cess Margaret Rose Hospital, Edinburgh during the 1960s. It was designed for children born with absent or malformed limbs. This was the result of their mothers taking the drug thalidomide during pregnancy.

Movements of this mobile arm prosthesis are controlled by movements of the muscles around the child’s shoulder blades. These movements are powered by compressed carbon dioxide. The gas is stored in cylinders in the ‘passive’ arm. An active child might use two gas cylinders per day. Such limbs were fitted to children from 18 months upwards. The arm prosthesis was developed by the Orthopaedic Bioengineering Unit at Prin-cess Margaret Rose Hospital, Edinburgh during the 1960s. It was designed for children born with absent or malformed limbs. This was the result of their mothers taking the drug thalidomide during pregnancy.

Lower limb prostheses, Roehampton, England, 1966

Pair of ‘swivel-walkers’ designed for a child born with no lower limbs, United Kingdom, 1966

Pair of artificial legs for a child affected by the drug thalidomide, England, 1968 -1972

Crash helmet, made for child affected by the drug thalidomide, England, 1967-1972

The drug thalidomide caused thousands of serious birth anomalies worldwide. Ba-bies were born with underdeveloped or missing limbs. Many pregnant women used the drug in the late 1950s and early 1960s. It eased morning sickness and aided sleep. This crash helmet was made for Eddie Freeman. He was a child affected by thalidomide. The helmet protected his head because he often lost balance while wearing artificial legs. Eddie eventually abandoned the helmet since he found it of limited use. The artificial limbs were made and fitted at Queen Mary’s Hospital in Roehampton, west London. Queen Mary’s opened in 1915. It became the main limb-fitting centre during and after the First World War. It dealt with just over half of the 41,000 British servicemen who lost a limb. Many children affected by thalidomide were fitted for artificial limbs at Roehampton. As they grew they returned to be fitted with new limbs.

The drug thalidomide caused thousands of serious birth anomalies worldwide. Ba-bies were born with underdeveloped or missing limbs. Many pregnant women used the drug in the late 1950s and early 1960s. It eased morning sickness and aided sleep. This crash helmet was made for Eddie Freeman. He was a child affected by thalidomide. The helmet protected his head because he often lost balance while wearing artificial legs. Eddie eventually abandoned the helmet since he found it of limited use. The artificial limbs were made and fitted at Queen Mary’s Hospital in Roehampton, west London. Queen Mary’s opened in 1915. It became the main limb-fitting centre during and after the First World War. It dealt with just over half of the 41,000 British servicemen who lost a limb. Many children affected by thalidomide were fitted for artificial limbs at Roehampton. As they grew they returned to be fitted with new limbs.

Five CO2 gas cylinders, 1962-1963

Movements of this mobile arm prosthesis are controlled by movements of the muscles around the child’s shoulder blades. These movements are powered by compressed carbon dioxide. The gas is stored in cylinders in the ‘passive’ arm. An active child might use two gas cylinders per day. Such limbs were fitted to children from 18 months upwards. The arm prosthesis was developed by the Orthopaedic Bioengineering Unit at Prin-cess Margaret Rose Hospital, Edinburgh during the 1960s. It was designed for chil-dren born with absent or malformed limbs. This was the result of their mothers taking the drug thalidomide during pregnancy.

Related links

Chemie Grünenthal GmbH

Food and Drugs Administration (FDA)

Frances Oldham Kelsey (1914-)

World Health Organisation (WHO)

Bibliography

A Leslie Florence, ‘Is Thalidomide to Blame?’, British Medical Journal, 2 (1960), p 1954

T Stephens and R Brynner, Dark Remedy: The Impact of Thalidomide and its Revival as a Vital Medicine (Massachusetts: Perseus Pub., 2001)

L Zichner, M A Rauschmann and K D Thomann (eds), Die Contergankatastrophe – EIne Bilanz nach 40 Jahren (Darmstadt: Steinkopff Verlag, 2005)

B Gault and H Rogers, Look, no Hands! The Inspiring Story of Brian Gault (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2000)

The Insight Team of the Sunday Times, Suffer the Children: The Story of Thalidomide (London: Andre Deutsch, 1979)

A Daemmrich, ‘A tale of two experts,’ Social History of Medicine, 15/1 (2002), pp 137-158

H Sjöstrom and R Nilsson, Thalidomide and the power of the drug companies (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972)